This article from Mary Heglar is a powerful, and worthwhile, thing to read. I’m not going to talk about it, because you can go and read it yourself – it isn’t long – but it reminded me of something I wrote a long time ago, on a blog far far away. It was just after the 2009 COP summit in Copenhagen, which was perhaps the first time that calls for climate action really became a mainstream mass campaign, rather than something for environmentalists. I’m going to quote some bits.

A lot of commenters are being despondent in the aftermath of COP-15. I can understand why, because it was the first climate summit where it had actually become a mainstream public issue, and the first in recent memory when a (arguably) sympathetic line from the White House meant that there was some chance of co-operation from the US. Additionally, time is pressing, and this was the first time so far as I remember that anybody had identified “this is what we need to aim for NOW”. Which we’re not going to do…

…I feel that while the solutions are technically within our grasp – just about – at present, there is no way that they are politically possible.

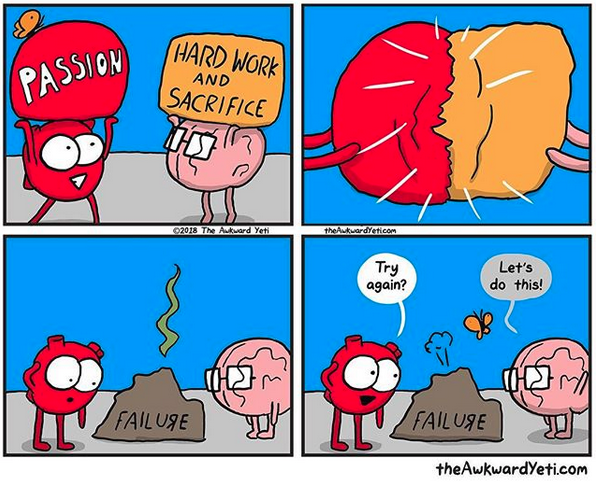

I’ve spent a certain amount of time thinking “If I think that the cause is hopeless, why am I wanting to work in the renewable energy and/or energy efficiency fields?”. The answer is that although the goals being debated at Copenhagen are politically hopeless, every little still helps……millions – if not billions – will suffer… but for every bit that we can reduce our emissions, less of this will happen. The fact that the situation is so terrifying, depressing, and hopeless… doesn’t mean that we can’t try to lessen it.

That… was a while ago. Time has moved on by a decade, and so has climate change. It’s reached a stage where effects are evident to many people. And perhaps partly because of this, and partly because of youth protests and Extinction Rebellion, and partly because of so many other people, the politics have moved on as well, to a place that I honestly didn’t think was possible just a few years ago. The support from the White House has vanished, but we’ve discovered that it wasn’t really needed after all.

In 2019, it’s probably too late to stick to a 2°C rise, let alone 1.5°C. We’re already well past the 350 or 400ppm that was being discussed in the run-up to Copenhagen. In that sense, we “lost”. But what I wrote in 2009 is still true: that that loss isn’t binary, and we can still influence how much worse things get.

As Heglar says in her article, simply giving up on the problem because we can’t totally avoid it is not helpful. Nor is criticising people for being optimistic. Or pessimistic. Or any other natural reaction that they may have. As a friend put it once, there’s a grieving process here, and everybody grieves differently. Recognising that climate change is going to have impacts, and putting effort into adapting to or mitigating those impacts, does not require us to give up on trying to limit the amount of change that is not yet locked in, but to do this we need to embrace everybody’s input[1], rather than shutting people down.

[1] That is, everybody who acknowledges that there is a problem.

This term, in addition to my modelling work at Marine Scotland, I’m the instructor for two masters modules at ICIT (Heriot-Watt’s Orkney campus). This is my first experience of teaching, beyond the occasional seminar here and there, and I’m really enjoying it. I have a small group of interested students, who want to be there (I realise that this is a privilege of teaching postgrad), who ask intelligent questions… and that makes it really rewarding.

This term, in addition to my modelling work at Marine Scotland, I’m the instructor for two masters modules at ICIT (Heriot-Watt’s Orkney campus). This is my first experience of teaching, beyond the occasional seminar here and there, and I’m really enjoying it. I have a small group of interested students, who want to be there (I realise that this is a privilege of teaching postgrad), who ask intelligent questions… and that makes it really rewarding.